The Lost Village of Hillam Burchard

THE LOST VILLAGE OF HILLAM BURCHARD

by Marolyn Piper

by Marolyn Piper

PLEASE RESPECT THE FACT THAT THE SITE IS ON THE PRIVATE LAND OF LEYFIELD FARM. THERE IS A PUBLIC FOOTPATH AND A BRIDLEWAY PASSING CLOSE BY BUT YOU SHOULD NOT WANDER OFF THEM.

Perhaps you may know that there were once medieval villages at Colton, Potterton, Lotherton and in the area around Lead Church (across from the Crooked Billet pub) – the field system associated with Lotherton is in the present Deer Park – but did you know that there was also a medieval settlement between Barwick and Aberford ?

The name of this settlement was Hillam Burchard. This article tries to give a flavour of what the settlement may have been like, based on what is known about it and research into similar medieval villages. References used are given at the end and special thanks are due to the helpful staff at W.Yorks Archaeology Service, Newstead House, Wakefield – where I was given access to the unpublished report on the investigations which took place in 1980 – and to David Berg of the Archive Service at Sheepscar who provided the photograph of “the pot”.

Hillam Burchard is not to be confused with the place called Hillam which is near Monk Fryston. The word Hillam is derived from “on the hills and the Burchard part of the name may have come from a twelfth century owner, son of Burgheard. The spelling of the settlement name was given as Hillome Buchard in a document of c1300 but as Hyllom Becharde in a document of c1401.

Our lost settlement was sited in fields to the east of Barwick – some 600 metres east of Ass Bridge and south of Cock Beck. As you go along the Barwick to Aberford Road the land rises to your left approaching Leyfield Farm and this is the area described. It seems that it also extended across the present road on the south side near to “Thru’penny Bit Lodge”. This area fell within the “Parlington” mentioned in the Domesday Book as variously Perlinctune/Perlintun/Pertilinctun/Pertilintun. Hillam Burchard was recorded as existing around 1144/1160AD but it may have existed in the 11th century or even earlier. There is evidence that Parlington contained two principal settlements – Parlington and Hillam Burchard. Why this site was chosen for settlement can only be speculation but it is obvious today that it would have been a pleasant area with convenient limestone, sandstone and water. The importance of its situation near water will become clear as we shall see.

The site extends over some 5 acres and was investigated in 1980 by the West Yorkshire County Archaeology Unit. Evidence of occupation was found dating occupation of the site from the twelfth to early fifteenth century. Over this long time a number of building phases took place and there may have been different “classes” of people living there – the quality of some domestic pottery remnants found there would indicate that some better off people may have lived there.

We are peering back a very long way – very little is known about what the houses of serfs (peasants) were like – most surviving medieval houses belong to the 15th century and were lived in by higher ranks of society.

No paper records are easily accessible for they didn’t exist then – the first references to villages is via the Domesday Book of 1086AD. Sometimes they are mentioned “in passing” via wills, records of disputes etc. It’s a case of putting together bits and pieces to try to get a picture.

We know that the houses of serfs would be constructed with a wooden frame covered with wattle and daub – probably a single room with a central hearth – maybe divided into two sections, one being for the family and one for any animals. Over time some houses were increased by the addition of further sections, perhaps for winter storage etc. We have to remember that Britain was very sparsely populated in these medieval times – somewhere around 3/5 million around 1250 -1300AD compared with around 60 million today ! In a survey made in 1425AD in the time of Henry IV, the population of the whole area around Barwick/Hillam was around 500/600 possibly equating to 150/200 dwellings in total. Death of women in childbirth was very high as was infant mortality and children would work alongside their parents from as early an age as they could.

Serfs were at the bottom of the feudal system and many worked in agricultural pursuits for their lord. Under the feudal system all land was ultimately owned by the King – he granted territories to his Earls and Barons in return for military aid in need. They in turn granted lands to men who fought for them – there was no standing army – and the basic administrative unit was the manor. A little land would be given to the serfs in return for their providing free labour, food and service to their lord as required. They generally had no rights, were not allowed to leave their manor and generally had a short, tough life !

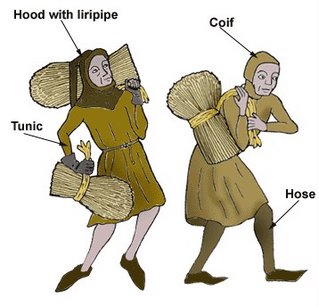

The women worked alongside the menfolk in addition to their household duties. The clothing in those times would have been very simple consisting for men of knee or calf-length tunic over hosen, for women a long tunic (ankle length). Both would have a white under-tunic which would be washed more frequently than the overtunic – which didn’t get washed much at all !! Men often wore a close fitting cap or hood and women perhaps a coif or hood.

We must try to imagine Hillam Burchard peopled with serfs going about their work – perhaps tending their own small garden areas, working on the fishponds or in the quarry, perhaps at the kiln or taking grain to the watermill. There would be few older people – the average life expectancy in 1276AD was 35.28 years – between 1301/1325AD during the great famine it was 29.84 years – whilst during the Black Death times of 1348/1375AD it was only 17.33 years !

We must try to imagine Hillam Burchard peopled with serfs going about their work – perhaps tending their own small garden areas, working on the fishponds or in the quarry, perhaps at the kiln or taking grain to the watermill. There would be few older people – the average life expectancy in 1276AD was 35.28 years – between 1301/1325AD during the great famine it was 29.84 years – whilst during the Black Death times of 1348/1375AD it was only 17.33 years !Some of the features revealed by the archaeologists were groups of banked enclosures, terraced platforms and terraced ways and hollow-ways situated on two projecting spurs of land on the south side of Cock Beck. The eastern group lay on the route to a water mill, this route following the slope of the valley to the mill situated some way to the north east.

In one area was a terraced yard, bounded by revetment walls and earthen banks, within which was a series of timberpost buildings and downhill from this area were a number of garderobe pits (toilets to you and me!).

To archaeologists, garderobe pits are a wonderful thing to discover – for they often contain “stuff” which was thrown away and gives up its secrets

to those who know how to interpret them !

In this case one of these pits produced this near-complete bowl of late 12th/early 13th century date.

In this case one of these pits produced this near-complete bowl of late 12th/early 13th century date.Another area contained a stone-lined lime burning kiln, and alongside the quarry was a multiphase rectangular building incorporating a square stone-built garderobe. The kiln was adjacent to the quarry and dug into the natural slope down to the sandstone bed. The walls were made from un-mortared limestone cut into regular brick-shaped blocks.

Lime (calcium oxide) was used for the manufacture of mortar and as a fertiliser –in medieval times it was discovered that lime improved soil structure and neutralised excessive soil acidity, leading to increased crop yields. Most medieval lime kilns were 10/12 feet in diameter, walled round to 3/4 feet high with draught tunnels at the base. Inside the kiln a fire of brushwood was made and broken limestone added to alternate layers with the fuel to the top of the wall and this was continued up to make a heaped top. The whole was covered with slabs of turf and left to burn for a week or two. By the 13th century lime kilns were being built with a tapering bowl-shaped interior with one or two drawholes or stokeholes at the base through which the fire was lit, fed and the ashes and lime extracted

The quarry cut through the outcrop of limestone through the shale beneath into the sandstone which was used for roof slates at that time. No fragments of roof slate were found on the site and no mortared walls so the materials produced must have been taken for other buildings in the area.

The method of forming the roof slates was probably by leaving the large blocks of stone out over winter so that the frost would “weather” them naturally and make them easier to be hand-split into slates. Many large fragments of slates in various stages of rough-out were found in the fill of the quarry. The slates to be used for roofing were called “thackstones”.

On the lower slopes were a series of earthworks representing enclosures, house platforms, terraced and hollow-ways as well as – what was to be probably the most exciting feature – a large fishpond complex.

The photograph above shows a similar complex as the actual photographs of Hillam Burchard are not clear enough to show up well – this photo is useful to give an idea of how they would look in our time from the air.

The photograph above shows a similar complex as the actual photographs of Hillam Burchard are not clear enough to show up well – this photo is useful to give an idea of how they would look in our time from the air.The fishpond complex had previously been thought to be a moat and is the largest medieval complex of its kind identified in West Yorkshire. Water from Cock Beck would have been passed through it and re-entered the beck by means of a weir, the earthworks of these still remained at the time of the survey. The complex was in the shape of 3 sides of a square, probably sub-divided by fencing, to form compartments for fish breeding. The fourth side, to the east, had 3 depressions which appeared to be separately built tanks. Access to the site appeared to be via a causeway at the eastern end of the southern arm from a terraced way running down the steep hillside from the mill route. The ponds were either shallow or badly silted up for they were only 1/1.5 metres deep at their centres.

The fish from these ponds were not destined for the serfs – perhaps they were allowed to have one or two – but were produced for the benefit of their lord primarily. Fish formed a good part of the diet of the upper classes in medieval times and fish breeding was also extensively carried out by monasteries. A constant flow of running water was required and many a dispute arose about unauthorised placing of fishponds.

(Interestingly a fishpond complex once existed in the boggy field across from the Crooked Billet – to the left of the small bridge which carries the bridleway over the small beck).The field gets waterlogged in heavy rain.

The diet of serfs would be simple - breads made from barley and rye baked into heavy dark loaves – peas and beans, which might be added to a sort of stew called pottage. This pottage would be whatever could be chucked in ! vegetables and, if they were lucky, a bit of salt pork or fatty bacon. Seasonal things like berries and nuts – anything edible which grew wild – would be gathered. If they had a little plot of land then they would grow whatever they could to supplement their diet ( From a survey of 1425 there are three small entries of interest – “Thomas Elis holds an acre of land and half an acre of meadow in Hillome” – “William Milner holds the pasture of Milneholme below the garden of Hillome…”

and “a small plot of pasture below the mill nil (no rent) because it is with the mill”).

There could be oatcakes cooked on the ashes of the fire or on hot stones and food would be well spiced as spices had been known since Roman times. Ale made from barley would be commonly drunk as much water was not drinkable. All in all the diet of serfs did not contain much protein and vitamins A,C and D were lacking so our serfs might feel hungry a lot of the time and must have always been anxious about food.

(The area next described is one which may be visited via the public footpath which leads there – you may go down the lane from the Barwick/Aberford road which leads to Leyfield Farm. A lane on the RH (not straight forward) leads down to the Cock Beck valley – there you will see the mill goyt to the immediate left of the bridge – the public footpath continues across the field. The boggy area was/is in the field to your left – the footpath will take you forward and slightly right eventually emerging on the bridleway known as Becca Lane where you may walk back to Aberford or up towards the A64. Please do not wander off the footpath !!)

Returning to our story – the second major feature, which would also have required a good supply of running water, was the mill. This mill, for grinding corn, was the property of the lord of the manor and persons living in the manor were obliged to use it and nowhere else. The mill was founded early in the 13th century and was sited east of the present farm- house in the valley of Cock Beck. There was a working mill on the site, known in later years as Becca Mill, well into the 19th century. The buildings disappeared by around 1930 and the site was levelled in the 1980s as part of a woodland management scheme.

Interestingly, in the survey of 1425 referred to earlier, there is a passage which says “there are 2 watermills of Hillome, sometime worth yearly beyond (after) deductions 50s 4d and nevertheless were farmed yearly at 60s, all outgoings such as mill wheels and all others to be found at the cost of the Lord”. Where the second mill may have been is unknown at this time and was not referred to in the archaeological report seen.

The original line of Cock Beck was altered to run a little further south and a short goyt cut to allow the water force to be controlled and thus drive a water wheel. There was a boggy area in the field to the north of the present line of Cock Beck which remained in the area approximately where the stream once ran and in wet weather would become a small shallow pond – a resident of Aberford remembers watercress growing in that area some 50 or so years ago. That this is the site of Hillam Mill is demonstrated by the goyt being dug to the south of the former stream course, within the territory of Hillam – had the mill been associated with Aberford the goyt would have been cut from the north line.

Many comings and goings could have been seen in this area (the route to the mill changed somewhat over the years since the final route cut across abandoned remains of the medieval settlement). It must have been extremely busy with horses and carts going along the millway – which survives intact for most of its length, except where it has become overgrown where it passes through woodland to the east and north of Leyfield Cottage.

A terraced way climbs the hillside to the east of the mill – ending in an enclosure with a pronounced bank on the east running down the hillside towards Cock Beck. A platform lies on a terraced area on the brow of the hill within the enclosure. These earthworks may be connected with the medieval mill site – perhaps the miller’s house – but they may be associated with the quarry to the west.

The lives of the inhabitants of this little settlement would have revolved around the changing seasons – and from about the late 12th century until 1751 the civil, ecclesiastical and legal year began on the 25th March, nearly 3 months later than the historical year. They would be constantly worried about the weather – a bad frost could leave a family or village without a crop for a year.

The Church (Catholic) played a major role in the lives of everyone for people believed that Heaven and Hell existed and were terrified of Hell – the control the Church had over people was total. Tithes had to be paid which would have been in goods if the serf had no money. The serf almost always had to pay in seeds, harvested grain, animals etc.

These tithes would be kept in tithe barns (it’s interesting to note that Aberford School was based on a redundant Tithe Barn and the school has a connection because of this to Oriel College, Oxford – which would merit a short article itself).

Both Aberford and Barwick Churches would have been familiar to those who lived in Hillam Burchard. Both had Churches on their present sites in medieval times, although they would have been smaller and simpler buildings then.

What caused this once thriving settlement, which had existed and changed over several generations, to be abandoned ? That question cannot be answered with certainty but some things known about this period suggest answers.

Scientists know that there was a Medieval Warm Period which lasted from approximately the 10th to the 13th centuries. During this time the seasons could be regularly relied upon in their effects. In the Domesday Book in the late 11th century vineyards were recorded in 46 places in southern England. The number grew by Henry VIII’s time to 139 sizeable vineyards in England and Wales. There is evidence for warm dry summers and mild winters during the period 1100 – 1200 AD.

There then followed a “Little Ice Age” – from 1250AD the Atlantic pack ice began to grow – around 1300AD dependable warm summers in Northern Europe ceased – in the years 1315/1317 there were Great Famines across this country and Europe. In the Spring of 1315 there was bad weather and crop failure lasted through 1316 until the summer of 1317. Europe did not recover until 1322. In England there were famines also in 1321, 1351 and 1369. All of society was affected but as serfs were 95% of the population they suffered most of all. Some estimates of the death toll in these famine periods put the totals at between 10% and 25% of the population !

The famines would have consequences for future events in the 14th century – for the Black Death would strike an already weakened population. The years of the Black Death were between c1338 and 1375.

Perhaps one or other of these events took their toll on our little settlement – it seems likely that the quarry had been backfilled before the end of the 15th century, giving a date probably before the mid 15th century for the abandonment of the eastern part of the site –for the quarry was dug across what would have been the main entrance to the site.

In some areas there were clearances by land owners – particularly by monasteries – who wanted to put sheep on the land. Sheep were very profitable and no account would be taken of anyone living on the land.

Perhaps one or other, or all these events in combination, brought about the abandonment of Hillam Burchard – only the Water Mill remaining.

Where might the final “resting place” of the inhabitants of our little settlement be ? In the medieval time, there would be very simple burials for poor people in their local Church graveyard. As has been recounted, only a very lucky man or woman made it into adulthood and lived much longer than 30 or so. It’s unlikely that any “grave goods” would be buried with the body, for people would not have been able to spare anything of much value, and the body would be laid in an east-west direction. Sometimes a few flowers might be interred. Sometimes a coffin would be used just as transport to the graveyard and the body removed from it for actual burial, allowing the coffin to be re-used by the community.

The Church had to be paid for baptisms, marriages and burials and you had to be buried in holy ground in order to get into Heaven.

Although these near-neighbours of ours lived such short and “narrow” lives, they were not necessarily brutish. There is a grave, at Wharram Percy abandoned village near Malton, of a mother with a tiny unborn baby. It seems most likely that the mother died of TB and an attempt was made to save the unborn child by performing a Caesarean – but the attempt failed. The two were laid tenderly together in the single grave.

Strange to think that our long-ago neighbours at Hillam Burchard would have had the same concern as people today in 2006 – the climate change and its effects on their lives and what the future held for their children. Did they wonder, as some of us do, if they would be remembered in the wide world around them ? Knowledge of them had faded, now we can glimpse them again – they reach out to us – forgotten no longer.

References/Publications Consulted

Deserted Villages by Trevor Rowley & John Wood

Excavations at Hillam Burchard Draft Report 1980 – by Stephen Moorhouse and Julian Henderson

W. York Archaeological Survey to 1500

Fishponds – Monuments Protection Programme

W. York Arch.Service Site and Monuments Records

Rescue News September 1980

Medieval Settlement in Yorkshire by S Moorhouse & West Yorks Metro County Council Archaeology Unit

Article in The Barwicker magazine

www.medievalgeneology.org.uk

www.historylearningsite.co.uk

1 Comments:

Great article. I just wanted to point out that, even with the life expectancy figures you gave, there would be plenty of older people around.

Remember, the figures you gave are AVERAGE life expenctancy. There was a terribly high rate ofinfant and child mortality in the Middle Ages, and all those dead children are included in the average for an area. For those medieval people who managed to live past age 10, it was likely they would live for a long time indeed. The exception of course is women dying in childbirth. It was far too common. But even so, some women and many men lived to be 50+ if they lived to reach puberty.

The typical serf would not die in his/her 30's. Instead they could brag, "Sure, my four brothers all died when they were kids, but I *never* get sick!"

Such was life.

By Anonymous, at 5:09 PM

Anonymous, at 5:09 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home